The Calf That Knew Her Cost of Gain

By Dr. Noah Litherland, Vita Plus dairy youngstock specialist

By Dr. Noah Litherland, Vita Plus dairy youngstock specialistOnce upon a time, near the northwoods of Dairyland, lived three nursery calves. They were congregating in their superhutch, chewing cud and reminiscing about days gone by in the cozy confines of their calf hutches. As often is the case, the calves started up a competitive and fun-loving conversation about who was the best nursery calf.

The first calf said, “Compared to the two of you, I was the best nursery calf because my feed costs during the nursery phase were the lowest.”

“Is that so?” asked the second calf. “Well obviously, I was the best nursery calf because I had the greatest average daily gain (ADG).”

The third calf swallowed her cud and said to the first calf, “I appreciate your thrifty ways because certainly feed costs are important,” and, turning to the second calf, she said, “Certainly your ADG is impressive, but I have been doing some figuring and I think my feed cost of gain were superior to both of you.”

The first two calves stood staring at the third calf with mouths agape and a bit of rumen foam dripping from the corners of the mouth.

The second calf whispered to the first calf, “What is she talking about? Whoever heard of cost of gain being important to dairy calves?”

The first calf thought for a minute and said, “Do you remember the other day when I squeezed through the slant rails at the feedbunk and went for a gallop around the farm?”

“Of course I remember! You kept bragging about how much narrower you were and how you could squeeze through the slant bars, you picked on me for my huge rumen and wide hips and how I couldn’t even begin to squeeze through.”

“Well, your rumen does look like you swallowed two 5-gallon buckets,” said the first calf.

“Do you have a point to this story?” asked the second calf.

“Oh yes! When I was galloping around the farm, I stopped at the feed shed to nibble on some grain and I overheard the steers, pigs, and chickens comparing their cost of gain,” said the first calf. “Apparently, it’s kind of a big deal.”

The first and second calf looked at the third calf and asked, “How do you know your cost of gain is better than ours?”

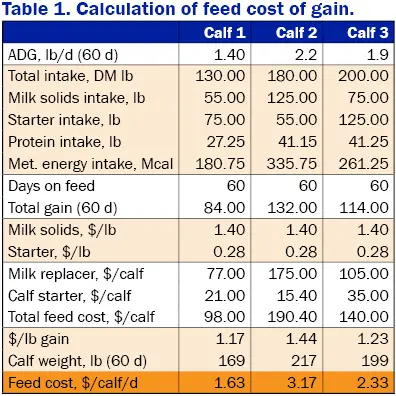

“That’s easy to figure,” said the third calf. “There are three simple numbers you need to know to calculate cost of gain.” She explained the three numbers are:

- How many pounds of weight did you gain during the nursery phase?

- How much of each feed (milk replacer or pasteurized milk, starter grain, and supplemental additives) did you eat?

- What is the cost per pound of each of these feedstuffs?

“That seems simple enough,” the first calf said. “If I shared my numbers with you, could you please show me how to calculate my cost of gain?”

“Sure,” said the third calf, and she whipped out her trusty spreadsheet and put her hooves to work to calculate cost of gain for her penmates (Table 1).

The third calf shared the results.

“WOW”, said the second calf, “my cost of gain is the highest!”

“And my cost of gain is the lowest!” said the first calf.

“Yeah, but you only weighed 169 pounds at 60 days of age”, said the second calf. “I weighed that much when I was only 40 days old!”

“These are all good observations,” said the third calf, “but my cost of gain is a reasonable $1.23 per pound. I am plenty large at nearly 200 pounds and I have been eating quite a bit of starter grain, so I am going to keep eating and growing through transition.”

“OK, cost of gain is easy to calculate, and it sure does show how our feed program is working,” said the second calf, “but please tell us how you got your cost of gain to be so competitive.”

“Yes, please tell us your secrets to having a low cost of gain and still being such a well-rounded and growthy calf,” pleaded the first calf.

Thus concludes the story of the calf who knew her cost of gain.

What is your nursery calf feed cost of gain?

Feed cost per pound of gain is an important metric to know how to calculate and manipulate to optimize the value of your nursery calf feeding program. Feed cost of gain during the nursery phase can vary greatly across feeding programs.

I use three key metrics to evaluate performance in a nursery calf program:

- Calf weight at 60 days

- Variation in calf weight at 60 days

- Feed cost per pound of bodyweight gain at 60 days

Feed costs, in the numerator, reflect both the total amount of feed allocated per calf and the respective cost of milk replacer or whole milk, additives, and starter grain.

Growth, in the denominator, represents the value gained from the feeding program. Feeding programs that yield greater growth without inflating feed costs result in decreased feed cost per pound of gain.

![]()

Key concepts

- The first 24 hours have a critical impact on response to feeding program and efficiency of growth.

- Calf health can have an overwhelming impact on maintenance costs and, therefore, cost of gain.

- Slow growth is expensive growth, especially when you consider labor for slow growth and fast growth are often similar.

- Growth from starter grain is always your best value because it has the lowest cost per unit of feed and results in gains rivaling growth from milk.

- When feeding pasteurized milk, use a value that reflects the cost of production and convert to a dry matter basis. For example, if whole milk is valued at $11 per hundredweight and is 12 percent solids, then 12 pounds of solids divided by $11 per hundredweight equals $1.09 per pound.

- The feed cost per gain calculation can more accurately reflect costs of production if you factor in feeding labor costs. Feed-and-labor cost of gain helps reflect costs associated with feeding frequency, feeding method, milk pasteurization, milk replacer mixing, and cleaning.

- Many feeding programs can work well, depending upon the intended outcome.

- Simply calculating cost of gain is a method of evaluating results of your feeding program.

| Category: |

Business and economics Calf and heifer nutrition Starting Strong - Calf Care |