Starch and moisture influences on CSPS (Chris Wacek-Driver with Kyle Taysom)

By Chris Wacek-Driver, Vita Plus forage program manager, with Kyle Taysom, Dairyland Laboratories, Inc.

By Chris Wacek-Driver, Vita Plus forage program manager, with Kyle Taysom, Dairyland Laboratories, Inc.The trend of feeding greater levels of corn silage to dairy cows and an influx of new processor designs has heightened dairy industry interest in determining optimal kernel processing. While it’s certainly not the sole factor that determines optimal dietary digestibility and utilization by the cow, kernel processing is an important consideration.

Corn silage: A complicated crop

By its nature, corn silage presents some unique challenges at harvest since it contains both corn grain and true forage (stalks and leaves). The particle size of both grain and true forage fractions are important for multiple reasons. From the cow’s point of view, the physical particle size of the grain affects the digestion of starch, and the particle size of the fiber affects its physical effectiveness in the rumen. Additionally, particle size affects pack density and fermentation in the storage structure. Finally, when the custom harvester is asked to produce specific particle sizes, additional cost may be added due to increased power, fuel and time requirements.

Simply said, corn silage is complicated.

Stepping back, more than half of the digested energy in corn silage comes from starch and sugars, located primarily in the corn kernel. Well-processed kernels are more readily digested, allowing more nutrients to be absorbed by the cow for milk production or weight gain. If we observe whole or half kernels in the silage, we know corn silage processing is less than ideal and starch may show up in the manure, either visually or in the form of a high fecal starch test at the lab.

Evaluating corn silage processing

As the popularity of feeding kernel processed corn silage increased in the late 1990s, a procedure was developed by to quantify kernel processing. The corn silage processing score (CSPS) uses a 12-hour drying period and aggressively shakes a sample through a set of nine sieves and a pan using a machine called the RoTap shaker. Based on the percentage of starch passing through the coarse screen, the sample is then assigned one of three rankings.

| Percent starch passing through coarse screen |

Ranking |

| > 70% | Optimum |

| 70 – 50% | Average |

| < 50% | Inadequately processed |

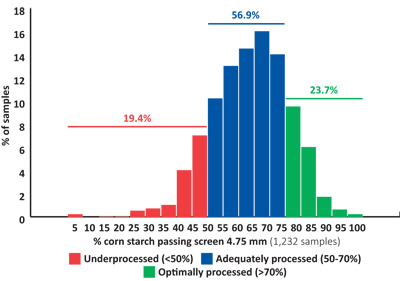

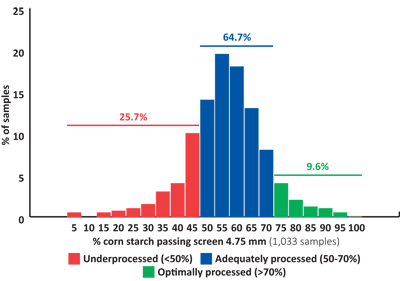

Analysis of data from samples submitted to Dairyland Laboratories, Inc. in Arcadia, Wisconsin from the crop years of 2009 to 2013 shows a trend toward improvement of kernel processing. Significantly fewer samples fall in the under-processed range and greater numbers of corn silage samples fall into the adequate and optimal range.

However, the limited number of corn silage samples falling in the optimal category underscores the challenges in attaining optimal kernel processing.

Several Vita Plus nutritionists were determined to attain better corn silage processing prior to ensiling. In the first attempt, nutritionists gathered fresh corn silage samples, counted whole and half kernels to estimate CSPS, and submitted the samples to Rock River Laboratory, Inc. in Watertown, Wisconsin for a CSPS lab result. A regression equation was developed based on the count of whole and half kernels.

In a second attempt, a separate group of Vita Plus nutritionists visually scored corn silage samples in the field by floating fresh corn silage samples in water as described by Shinners and Holmes (University of Wisconsin) with a duplicate fresh corn silage sample sent to Dairyland Laboratories for CSPS determination.

In both attempts, the relationship between the field methods and the actual laboratory CSPS scores were quite variable and highly influenced by the attending nutritionist. This suggests a “human element” in trying to assign CSPS under field conditions and the person assigning the CSPS accounts for variance in CSPS. Both of these projects illustrate that quick, on-farm methods to determine CSPS during harvest are challenging to do.

As a result, rather than try to quantify a specific “corn silage processing score” during harvest, we really may only be able to separate fresh corn silage into general categories (inadequate, adequate or excellent).

Factors influencing digestibility

In 2014, as corn silage harvesters were trying to adequately process silage with varying maturity, moisture, and starch content, we came across several questions. After harvest, we took some time to seek more information within a large dataset of CSPS results from Dairyland Laboratories.

The first question we asked was, “How does whole-plant moisture influence lab CSPS scores?” From September 2008 through February 2014, 4,058 samples have been run for CSPS. Using this dataset, “normal” corn silage was defined as corn silage containing 63 to 68 percent moisture, wet corn silage as greater than 68 percent moisture, and dry corn as less than 63 percent moisture. The data indicated wet corn silage samples did not score as well as dry corn silage samples and shifted the distribution of corn silage processing scores.

Dry <63% moisture

Wet >68% moisture

The drier the corn silage, the better the corn silage processing. In contrast, the wet corn silage produced lower corn silage processing scores.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. While CSPS reflects the particle size of starch, certainly many of the wetter corn silages contained immature, milky kernels, which should contain highly digestible starch. Research data supports this observation and suggests CSPS is less important when corn silage is wetter, but becomes more important as the corn plant matures (dries).

Another question raised was: Is it possible for the immature starch to stick to forage fiber, even when run through an oven-drying procedure designed to separate the fine starch from the forage fraction? While never fully researched, key researchers have suggested limitations of the CSPS scoring when done on wet corn silage samples (Dave Mertens, USDA Dairy Forage Research Center, and Pat Hoffman, University of Wisconsin).

Since drier corn silage often contains more mature kernels – and thus more starch – is it reasonable to assume that the mature kernels shatter better? Perhaps the hardness and size of mature kernels make them more likely to shatter during processing? Or are corn silage harvesters processing drier corn silage more aggressively because they know it’s more important?

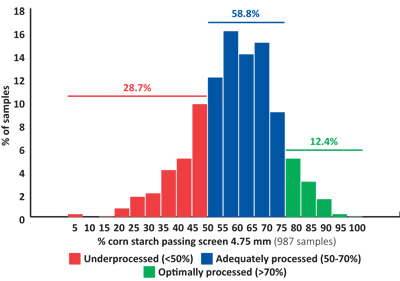

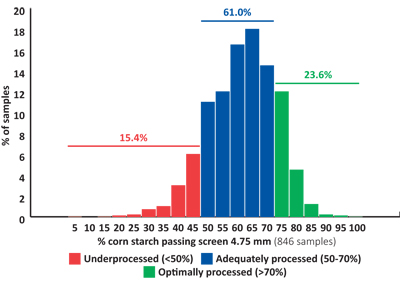

Low starch <30%

High starch >37%

Using the same data set, normal corn silage was defined as 30 to 37 percent starch, low-starch silage as less than 30 percent starch, and high-starch silage as containing greater than 37 percent starch. It was observed that low-starch corn silages had lower CSPS scores as compared to high-starch corn silage samples, and shifted the data to less processed.Low-starch corn silage often corresponds with less mature corn silage, in which softer, wetter kernels would be processed. Unfortunately, trying to further tease out all of the differences in CSPS due to differing starch or moisture contents is challenging because, in many ways, they are inherently related.

CSPS is an important evaluation tool on dairy farms and interest in this measurement has increased. While CSPS is important tool, it still remains only a benchmark of corn silage quality and it should be used in conjunction with common sense, other sources of information, and economic considerations.

| Category: |

Equipment Feed quality and nutrition Forage Foundations Forage harvesting |