Make the right decisions for harvesting drought-stressed corn silage

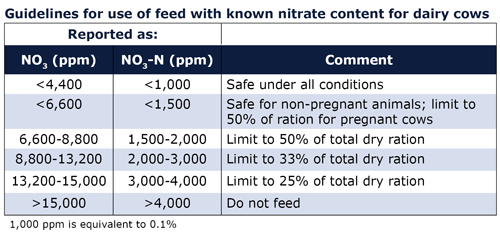

By Chris Wacek-Driver The drought conditions we’re seeing have many of us worrying about this year’s yields. It is extremely difficult and emotionally challenging to watch a valuable and needed crop curl and turn brown due to lack of moisture. While the gut tendency may be reactive based on visual information, careful analysis and informed decision-making need to rule. When it comes to harvesting drought-stressed corn silage, the key is to harvest at the proper moisture content. For corn silage, that moisture is 60 to 67 percent. Going above that level is detrimental due to excess nutrients (including sugar) in the runoff. On the flip side, ensiling at too dry of moistures will restrict fermentation and possibly increase the nitrates in the plant. Plus it’s more difficult to pack and is likely to have reduced bunk life. Determining moisture content Visual estimates of moisture content are inaccurate. The plant may look dry, but still contain significant moisture in the stalk. Additionally, drought stress will pull out differences in hybrids and soil conditions. It is likely you will see a lot of variation. Monitor moistures often and among different fields and hybrids. Once you believe moisture levels are close to the target range, the best method for determining moisture is to chop part of a load. Moisture needs to be monitored closely since drought-stressed corn can drop in moisture quickly, sometimes by as much as a point or two a day. Nitrates As previously mentioned, nitrates can be high in drought-stressed corn. Testing is relatively inexpensive and recommended. Symptoms of nitrate toxicity include an increased pulse rate, increased respiration, muscle tremors, staggering and blindness. The table below offers guidelines for nitrate content in corn silage fed to dairy cows.

By Chris Wacek-Driver The drought conditions we’re seeing have many of us worrying about this year’s yields. It is extremely difficult and emotionally challenging to watch a valuable and needed crop curl and turn brown due to lack of moisture. While the gut tendency may be reactive based on visual information, careful analysis and informed decision-making need to rule. When it comes to harvesting drought-stressed corn silage, the key is to harvest at the proper moisture content. For corn silage, that moisture is 60 to 67 percent. Going above that level is detrimental due to excess nutrients (including sugar) in the runoff. On the flip side, ensiling at too dry of moistures will restrict fermentation and possibly increase the nitrates in the plant. Plus it’s more difficult to pack and is likely to have reduced bunk life. Determining moisture content Visual estimates of moisture content are inaccurate. The plant may look dry, but still contain significant moisture in the stalk. Additionally, drought stress will pull out differences in hybrids and soil conditions. It is likely you will see a lot of variation. Monitor moistures often and among different fields and hybrids. Once you believe moisture levels are close to the target range, the best method for determining moisture is to chop part of a load. Moisture needs to be monitored closely since drought-stressed corn can drop in moisture quickly, sometimes by as much as a point or two a day. Nitrates As previously mentioned, nitrates can be high in drought-stressed corn. Testing is relatively inexpensive and recommended. Symptoms of nitrate toxicity include an increased pulse rate, increased respiration, muscle tremors, staggering and blindness. The table below offers guidelines for nitrate content in corn silage fed to dairy cows.  Nitrates are found in the stalk, stem and leaves of the plant, but usually concentrated in the lower one-third of the stalk. Fermentation generally reduces nitrates by 40 to 50 percent and a high quality inoculant will aid in that reduction. Since fermentation is the best way to reduce nitrates, we recommend allowing corn silage to ferment at least three weeks before feeding. Longer is better. If we see a heavy rainfall prior to harvest, we recommend waiting an extra five to seven days to harvest. If you allow cows to graze or you green-chop the corn silage, it needs to be tested for nitrate accumulation. If put up as silage, it is still highly advisable to test prior to feeding. However, fully fermented forages are generally within the limits of being safe to feed. Inoculants Generally, as long as it’s at the right moisture, drought-stressed corn silage will ferment well. The single biggest mistake is to put it up too wet. This will result in very acidic silage that’s especially high in acetic acid. This poor fermentation will almost certainly compromise animal performance. It is highly recommended to use a high quality bacterial inoculant. UV light often reduces the number of natural organisms on the crop. Having an adequate number of organisms for fermentation helps reduce the potential nitrates. Additionally, mounting scientific evidence and field observations clearly show that controlling the fermentation under hot conditions is tough. We do not recommend using an NPN source for drought-stressed corn silage because of the increased possibility of elevated nitrate levels. Nutrient content changes Crude protein will be increased and, due to poor ear fill, starch content will be reduced. However, high sugar levels are likely because those sugars won’t be converted to starch. Fiber levels will be elevated, but often be more digestible. Depending on the degree of the drought stress, energy value can be 65 to 100 percent of normal corn silage. Be safe No matter what the conditions, your number one priority for harvesting corn silage should be safety. With drought-stressed corn silage, we see an increased risk of silo gases, which are heavier than air and can be lethal to humans and livestock. Some gases are yellow or orange, but others are odorless and colorless. Be cautious and follow these safety guidelines when putting up silage:

Nitrates are found in the stalk, stem and leaves of the plant, but usually concentrated in the lower one-third of the stalk. Fermentation generally reduces nitrates by 40 to 50 percent and a high quality inoculant will aid in that reduction. Since fermentation is the best way to reduce nitrates, we recommend allowing corn silage to ferment at least three weeks before feeding. Longer is better. If we see a heavy rainfall prior to harvest, we recommend waiting an extra five to seven days to harvest. If you allow cows to graze or you green-chop the corn silage, it needs to be tested for nitrate accumulation. If put up as silage, it is still highly advisable to test prior to feeding. However, fully fermented forages are generally within the limits of being safe to feed. Inoculants Generally, as long as it’s at the right moisture, drought-stressed corn silage will ferment well. The single biggest mistake is to put it up too wet. This will result in very acidic silage that’s especially high in acetic acid. This poor fermentation will almost certainly compromise animal performance. It is highly recommended to use a high quality bacterial inoculant. UV light often reduces the number of natural organisms on the crop. Having an adequate number of organisms for fermentation helps reduce the potential nitrates. Additionally, mounting scientific evidence and field observations clearly show that controlling the fermentation under hot conditions is tough. We do not recommend using an NPN source for drought-stressed corn silage because of the increased possibility of elevated nitrate levels. Nutrient content changes Crude protein will be increased and, due to poor ear fill, starch content will be reduced. However, high sugar levels are likely because those sugars won’t be converted to starch. Fiber levels will be elevated, but often be more digestible. Depending on the degree of the drought stress, energy value can be 65 to 100 percent of normal corn silage. Be safe No matter what the conditions, your number one priority for harvesting corn silage should be safety. With drought-stressed corn silage, we see an increased risk of silo gases, which are heavier than air and can be lethal to humans and livestock. Some gases are yellow or orange, but others are odorless and colorless. Be cautious and follow these safety guidelines when putting up silage:

- Use a blower to ventilate the silo for a minimum of 30 minutes before entering and keep the doors closed while you’re ventilating. (The heavy gas will sink. If the doors are open, ventilation will push the gas toward you in high enough amounts that it can cause serious respiratory problems and/or death.)

- Keep fans running the entire time you’re in the silo.

- Avoid entering the silo after harvest. By the time you realize you are exposed to silo gas, you will likely be too weak to climb out of the silo.

- If you see or smell gas at any time, get out immediately. The same rules apply if you start to feel any irritation of the throat or lungs.

- Be cautious in opening newly filled bags, piles or bunkers, particularly if they have been well sealed or are covered with oxygen-barrier plastic.

- Most importantly, tell someone if you will be working in or around a silo so that he or she can watch out for you and call for help in the event of an accident.

About the author: Chris Wacek-Driver is the Vita Plus forage program manager. She grew up on a farm outside of Denmark, Wis. and attended the University of Wisconsin-River Falls where she earned her bachelor’s degree in dairy science with an ag business minor. She went on to receive her master’s degree from UW-Madison. She conducted her research focusing on forage quality at the USDA Forage Center under Dr. Larry Satter. In particular, she studied forage fermentation, the role of microbial and enzyme additives, and their effects on dairy animal performance. Wacek-Driver has been a Vita Plus employee owner for the past 21 years and worked in dairy technical services prior to her current role. She has a passion for working with dairy producers to help them with on-farm feed inventory, feed management, forage fermentation and production, and dairy nutrition. She resides on a 240-acre farm along the bluffs of the Mississippi River in western Wisconsin.

| Category: |

Dairy Performance Drought Forage harvesting |