Preserve homegrown nutrients for milk production

A herd’s potential for milk production is greatly influenced by the quality of forages we put in storage and how well we preserve them.

One of the most important things we can do to achieve these goals is to drive a rapid and efficient drop in pH once we put the feed in the silo, bunker or pile. This drop in pH prevents growth of undesired bacteria and preserves valuable nutrients. As the fermentation process begins, lactic acid-producing bacteria consume sugars, starches, and proteins and convert them to lactic acid. The lactic acid lowers the silage pH which stops bacterial and yeast activity.

We want upfront fermentation – and the subsequent drop in pH – to occur as quickly as possible. The longer it takes, the more nutrients get consumed by bacteria. Consider a haylage that is 40% dry matter (DM) and valued at $92 per ton (as fed). For every 1% increase in DM loss, you lose almost $1 worth of feed per as-fed ton. That means, in a 5,000-ton bunker, every 1% increase in shrink is a loss of $5,000. Shrink on a pile can easily vary by more than 20%. Shrink means we pay more for a less valuable feedstuff, impacting income over feed costs.

Harvesting and packing

It’s critical to harvest forage at the proper DM content to drive a rapid drop in pH.

When a silage is too wet, detrimental bacteria (such as Clostridia) can dominate the fermentation. These bacteria consume high-quality nutrients (lactic acid, protein, etc.) and produce harmful metabolic end products, such as biogenic amines.

When a silage is too dry, it does not pack as well and allows for greater oxygen penetration, bacterial growth and less efficient lactic acid production. During the aerobic phase of ensiling, bacteria consume oxygen and silage nutrients and produce heat, carbon dioxide, and water. Once oxygen is eliminated and the silo enters the anaerobic phase of ensiling, the activity of most bacteria and yeast ceases.

Challenges of delayed sealing

Seal the bunker or pile as quickly as possible so that oxygen does not continue to infiltrate the silage mass. Even on a well-packed pile, when feed is not covered quickly, oxygen can penetrate the surface several feet, especially in the outer edges of piles. As long as oxygen is present in the feed, bacteria will continue consuming nutrients, including sugars and proteins that fuel lactic acid-producing bacteria, thus slowing lactic acid production and the subsequent pH drop. This often leads to a higher silage pH and a less-stable pile. Using a quality oxygen barrier plastic can reduce DM loss in the top 3 feet by 40% compared to an uncovered pile and by 10% compared to a conventional 5-mil plastic cover and tires.

Frequently, bunkers and piles cannot get covered right away due to difficult or dangerous environmental conditions. Loss of daylight and a fatigued harvest crew can make for a dangerous situation. Protecting the safety of all farm team members is always the most important task in forage harvest and storage.

A recent Vita Plus trial shows that another tool in the silage production toolbox can help preserve nutrients.

In this trial, triticale with 26% DM was ensiled in bucket silos, replicating a difficult ensiling scenario. One set of the bucket silos was sealed immediately, and the other set remained open for 24 hours before being sealed. Silages were untreated or treated with an upfront fermenter, which contains Lactobacillus plantarum MTD/1®, a lactic acid-producing inoculant bacterium. All silos were opened after 124 days and analyzed.

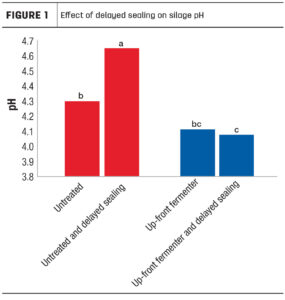

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, delayed sealing of the untreated silage led to a significantly higher pH and a significantly higher level of butyric acid. The higher pH makes the silage more prone to spoilage, with less sugar and starch available for cows to utilize. Butyric acid is not palatable and is highly likely to reduce intake. Spoilage microorganisms may also produce biogenic amines, such as putrescine and cadaverine, creating silage that may be dangerous to feed to cows.

In contrast, the trial showed that silage inoculated with a high-quality upfront fermenter had a lower pH and no butyric acid – even when sealing was delayed.

Maximizing homegrown nutrients is key to improving income over feed costs. Invest the time to create a forage harvest and storage plan that will allow you to preserve as many nutrients as possible while also limiting potential spoilage. Take advantage of technologies proven to improve DM recovery and reduce spoilage, even when conditions are not ideal. And, finally, remember that keeping your team safe is the most important goal.

This article was originally published in the July 19, 2024, issue of Progressive Forage. Click here to read more.

| Category: |

Forage Foundations Forage harvesting Forage storage and management Silages |