Aflatoxin: No room for error in dairy

Posted on September 20, 2012 in Dairy Performance

By Dr. Al Schultz and Rod Martin

By Dr. Al Schultz and Rod MartinAlmost every year at harvest, we have a few conversations about common molds and mycotoxins. However, this year’s weather events have pushed us to look closer at a mycotoxin that isn’t as common in the upper Midwest: aflatoxin. Aflatoxin is produced by the Aspergillus mold. It thrives in periods of excessive heat and drought conditions, which is why it’s of particular concern to producers this harvest season. Spores travel by the wind and infect silks or kernels, usually through insect wounds. Aflatoxin is considered carcinogenic (cancer-causing) to animals and potentially humans. For that reason, aflatoxin contamination is highly regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

How much is too much?

When aflatoxin-contaminated feeds are ingested by dairy cows, the toxin can be absorbed by the animals and enter the milk. FDA requires that all milk contain less than 0.5 ppb aflatoxin. Any milk above that level must be dumped. It is estimated that the absorption rate of dietary aflatoxin is between 1.75 and 2.0 percent. Thus, to stay below the maximum limit of 0.5 ppb, the overall dietary concentration cannot be higher than 25 to 30 ppb.

When aflatoxin-contaminated feeds are ingested by dairy cows, the toxin can be absorbed by the animals and enter the milk. FDA requires that all milk contain less than 0.5 ppb aflatoxin. Any milk above that level must be dumped. It is estimated that the absorption rate of dietary aflatoxin is between 1.75 and 2.0 percent. Thus, to stay below the maximum limit of 0.5 ppb, the overall dietary concentration cannot be higher than 25 to 30 ppb.

Is it in my feed?

We have heard isolated reports of some aflatoxin levels as high as 300 ppb in individual feeds. However, these levels vary greatly from field to field and even plant to plant. Also consider that, although your fields appear aflatoxin-free, your feeds may still be at risk for contamination if you are feeding byproducts that originated in drought and heat-stressed areas. Some suppliers are checking and rejecting corn with high levels of aflatoxin, but that may not be the case for all suppliers. This includes ethanol plants. Iowa State University estimates that “aflatoxin levels in feed co-products will be four times those in whole corn.”

We have heard isolated reports of some aflatoxin levels as high as 300 ppb in individual feeds. However, these levels vary greatly from field to field and even plant to plant. Also consider that, although your fields appear aflatoxin-free, your feeds may still be at risk for contamination if you are feeding byproducts that originated in drought and heat-stressed areas. Some suppliers are checking and rejecting corn with high levels of aflatoxin, but that may not be the case for all suppliers. This includes ethanol plants. Iowa State University estimates that “aflatoxin levels in feed co-products will be four times those in whole corn.”

How do I test my corn grain for aflatoxin?

You may have heard of using a black light to detect aflatoxin in corn grain. That’s because the Aspergillus mold also produces a compound called kojic acid under certain conditions. Kojic acid will fluoresce as bright green-yellow under a UV light. The catch is that these two compounds – aflatoxin and kojic acid – are produced independently of each other. The mold may produce substantial quantities of kojic acid and no aflatoxin. Conversely, it may produce detrimental levels of aflatoxin and no kojic acid. Thus, a black light is best used as an alert system. The best way to test for aflatoxin is to send a representative sample to a lab. Note that several labs are offering discounted pricing for aflatoxin screening through the end of the year. Proper sampling is critical. As recommended by the University of Arkansas, “take at least 8 to 12 samples at each of 3 to 5 locations in the feed bin or trough. Mix the sub-samples and take a two-pound composite sample. Store one sample in a cool, dry place, and use the other one for testing…The second one-pound composite sample may be used for possible confirmatory testing.”

You may have heard of using a black light to detect aflatoxin in corn grain. That’s because the Aspergillus mold also produces a compound called kojic acid under certain conditions. Kojic acid will fluoresce as bright green-yellow under a UV light. The catch is that these two compounds – aflatoxin and kojic acid – are produced independently of each other. The mold may produce substantial quantities of kojic acid and no aflatoxin. Conversely, it may produce detrimental levels of aflatoxin and no kojic acid. Thus, a black light is best used as an alert system. The best way to test for aflatoxin is to send a representative sample to a lab. Note that several labs are offering discounted pricing for aflatoxin screening through the end of the year. Proper sampling is critical. As recommended by the University of Arkansas, “take at least 8 to 12 samples at each of 3 to 5 locations in the feed bin or trough. Mix the sub-samples and take a two-pound composite sample. Store one sample in a cool, dry place, and use the other one for testing…The second one-pound composite sample may be used for possible confirmatory testing.”

What are my feeding options?

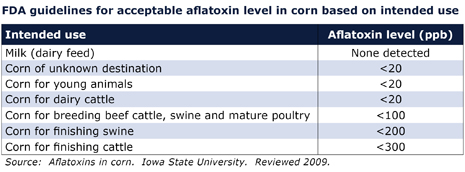

First, timely harvest and proper storage is of the utmost importance. If you suspect aflatoxin in a field, harvest there first and get the corn drying. It’s critical to maintain low moisture levels of 13 to 15 percent. A storage temperature below 40°F is ideal if weather permits. You have a few different options for managing aflatoxin in your feeds. Depending on feeding rates, you might be able to dilute the feed if the aflatoxin is at a manageable level. Research trials have shown that certain feed ingredients may bind the aflatoxin. You may want to include these ingredients in the diet. Work with your nutritionist to determine what product best fits your situation. Second, you may divert the grain to be fed to other species less susceptible to aflatoxin. (Note that the FDA has established an “action level” of 20 ppb for aflatoxin in corn that is sold across state borders.) See the table below:

First, timely harvest and proper storage is of the utmost importance. If you suspect aflatoxin in a field, harvest there first and get the corn drying. It’s critical to maintain low moisture levels of 13 to 15 percent. A storage temperature below 40°F is ideal if weather permits. You have a few different options for managing aflatoxin in your feeds. Depending on feeding rates, you might be able to dilute the feed if the aflatoxin is at a manageable level. Research trials have shown that certain feed ingredients may bind the aflatoxin. You may want to include these ingredients in the diet. Work with your nutritionist to determine what product best fits your situation. Second, you may divert the grain to be fed to other species less susceptible to aflatoxin. (Note that the FDA has established an “action level” of 20 ppb for aflatoxin in corn that is sold across state borders.) See the table below:

Another option is to clean or screen the product as aflatoxin is often present at the highest concentration in broken and cracked kernels. However, research shows that aflatoxin levels are not always significantly reduced following cleaning in highly contaminated lots. Lastly, roasting corn at 290 to 330°F can reduce the aflatoxin content by 40 to 80 percent. However, these temperatures are higher than those used in the normal corn roasting process and some loss in feed value can be expected.

What if aflatoxin shows up in my milk?

Aflatoxin is a serious issue for dairy and can have a significant economic impact. Once you start feeding corn with a high level of aflatoxin, the milk level goes up almost immediately. However, it may take four to five days after you eliminate the contaminated feed for the milk aflatoxin level to clear the animal’s system. This depends both on the concentration of aflatoxin and the diet being fed. As recommended by the University of Arkansas, “if aflatoxin is detected in milk, it is critical that records be maintained of all feeds, feeding practices, milk quantities and contamination levels, plus animal health and performance.” If your milk exceeds the allowable limit, all grain products should be removed from the ration immediately. Again, work with your consultant to develop the best plan of action for your farm. The following university publications can offer more insight into aflatoxin issues and regulation:

Aflatoxin is a serious issue for dairy and can have a significant economic impact. Once you start feeding corn with a high level of aflatoxin, the milk level goes up almost immediately. However, it may take four to five days after you eliminate the contaminated feed for the milk aflatoxin level to clear the animal’s system. This depends both on the concentration of aflatoxin and the diet being fed. As recommended by the University of Arkansas, “if aflatoxin is detected in milk, it is critical that records be maintained of all feeds, feeding practices, milk quantities and contamination levels, plus animal health and performance.” If your milk exceeds the allowable limit, all grain products should be removed from the ration immediately. Again, work with your consultant to develop the best plan of action for your farm. The following university publications can offer more insight into aflatoxin issues and regulation:

-

“Aflatoxins in corn” produced by Iowa State University

-

“Aflatoxin M1 in milk” produced by the University of Arkansas

About the authors: Dr. Al Schultz is vice president of Vita Plus and has been an employee owner for more than 35 years. Schultz grew up in eastern Wisconsin on a registered Holstein dairy farm. One of his “claims to fame” is the family showing of the Grand Champion Holstein cow at the 1968 World Dairy Expo. He has earned all of his degrees in dairy science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Currently, Schultz oversees activities related to product formulation, quality control and regulatory issues. In addition, he works closely with the dairy team and has corporate responsibilities. He lives with his wife in Verona, Wis. His two grown children and their spouses include a diverse mix of a teacher, lawyer, airline pilot and doctor. Rod Martin is a dairy specialist and a member of the Vita Plus dairy technical services team. He grew up on his family’s diversified livestock farm in southwest Wisconsin and attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in agricultural education and animal science, and a master’s degree in animal nutrition. He has 24 years of experience in consulting with Midwest dairy operations.

| Category: |

Animal health Dairy Performance Mycotoxins Silages |