Midd I ask you?

By Jessica Boehm and Julie Salyer

By Jessica Boehm and Julie Salyer

When do you include wheat midds into the diet? This is a common question with the prices of corn and soybean meal on the rise. As prices increase, we start to look at other feedstuffs that can be incorporated into swine diets.

What are these products and why should we look to them as potential sources of nutrients for our pigs?

Wheat middlings, commonly referred to as wheat midds, are born from the process of milling wheat into flour. Since this process is not 100-percent efficient, millers are left with 25 to 30 percent leftover byproducts. These products include:

- Wheat bran – This is the outermost layer of the wheat kernel. It contains approximately 16 percent protein, but is high in fiber and low in digestible energy. Thus, it may potentially work as a feedstuff for sows, but it is generally not great for most swine diets.

- Wheat shorts – This is the fraction from the inner layers of the seed coat. It contains starchy components, but has a lower fiber content than the bran.

- Wheat midds – This is an intermediate fraction that is thought to be somewhere in the middle between the bran and the shorts. Hence the term “middlings.”

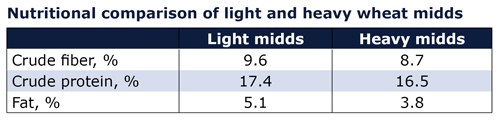

As with any byproduct, wheat midds have extremes in quality and composition. From mill to mill and even batch to batch, we see a lot of variation among wheat middlings samples. However, research by Cromwell has shown that bulk density can be a tool for quickly estimating potential nutritional value:

- Light midds (between 18 and 20 pounds per cubic foot) contain more bran

- Heavy midds (between 22 and 24 pounds per cubic foot) contain more shorts

Cromwell, et al., 1992. Wheat middlings in diets for growing-finishing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 70 (Suppl. 1):239 (Abstr.).

Wheat midds can be used in swine diets and are valuable for their energy and protein content. A rule of thumb for wheat midd inclusion is that 100 pounds of wheat midds will replace 86.5 pounds of corn, 12 pounds of high protein soybean meal and 1.5 pounds of monocalcium phosphate. This swap will replace the lysine and phosphorus that was supplied by the corn and bean meal. In terms of energy in the diet, this will only be lowered by 15 kcals of metabolizable energy per ton.

Experiments have shown that, as dietary wheat midds are increased in the diet, we observe a linear decrease in ADG and feed conversion. The majority of studies measuring carcass traits also reported a decrease in carcass yield. This decrease can be due to both the increased gut fill and decreased leanness in pigs fed higher fiber diets.

Therefore, pig flow and pig space requirements need to be evaluated when considering the inclusion of wheat midds into your swine diets. Generally, wheat midds can be included up to 5 percent of the diet for nursery pigs and lactating sows, and up to 25 percent or more for growing and finishing pigs. For gestating sows, there appears to be no limit for inclusion rate provided the diet is balanced properly.

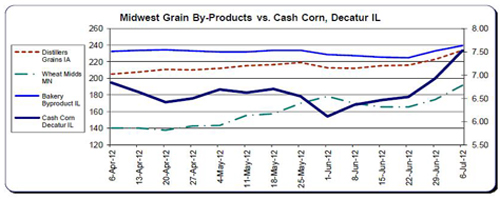

Pricing and availability of wheat midds is the next consideration, and it’s often the most important factor when deciding whether to include this product in the diet. Since wheat midds are a byproduct of producing flour, the supply is based on flour production. As a general rule of thumb, the price of wheat midds decreases during the spring and summer months and is highest in the fall and winter. The price also depends largely on the markets for beef and dairy feedstuffs as this ingredient is generally a better fit for those animals.

We are constantly looking at alternative feedstuffs as the price of corn and soybean meal swing; however, the other feedstuffs tend to follow corn. In other words, as corn prices increase, so too do the prices of alternative ingredients.

Graph from July 6, 2012 edition of the Feed Ingredient Weekly by Informa Economics, Inc.

As with all by product opportunities, you need to carefully evaluate price and quality of wheat midds before making a switch in your pigs’ diet. Work with your nutritionist to develop a strategy that works best for your operation and goals.

About the authors: Jessica Boehm previously worked as the Vita Plus swine technical information specialist. She attended the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point and earned a bachelor’s degree with a major in biology and minor in chemistry and psychology in 2006. She earned her master’s degree in swine nutrition at UW-Madison in 2009. She was raised in southern Wisconsin and spent her time on the family farm, raising veal, sheep, steers, pigs and tobacco. Boehm is active in her community and on the family farm, and enjoys outdoor activities and spending time with her husband, Justin. Julie Salyer previously provided technical support for Vita Plus field and sales staff and conducted nursery research trials as a swine nutritionist. Salyer received her bachelor’s degree at The Ohio State University and master’s degree in swine nutrition at Kansas State University. She is originally from southwest Ohio, where she raised and showed livestock for the county 4-H fair. She was also a student worker at Ohio State’s swine farm and completed an internship in North Carolina for Murphy Brown LLC, which she says was instrumental to where she is today. Salyer is active in church and enjoys hunting, kayaking, hiking and spending time with her husband, Brandon, and their two dogs.

| Category: |

Corn and soybeans Feed costs Feed ingredients Swine Performance |