Overview of the Canadian Pork Industry – Part two

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a three-part series comparing the Canadian pork industry to the U.S. pork industry.

Editor’s note: This is the second article in a three-part series comparing the Canadian pork industry to the U.S. pork industry.

By Garrett Rozeboom

In part one of this series, I compared the exports, imports, and hog census data of the U.S. and Canadian pork industries. Regardless of the differences, both countries benefit from the other. In this second part, I will discuss the differences and similarities in swine diet ingredients and formulation methodologies used in both countries.

Ingredients

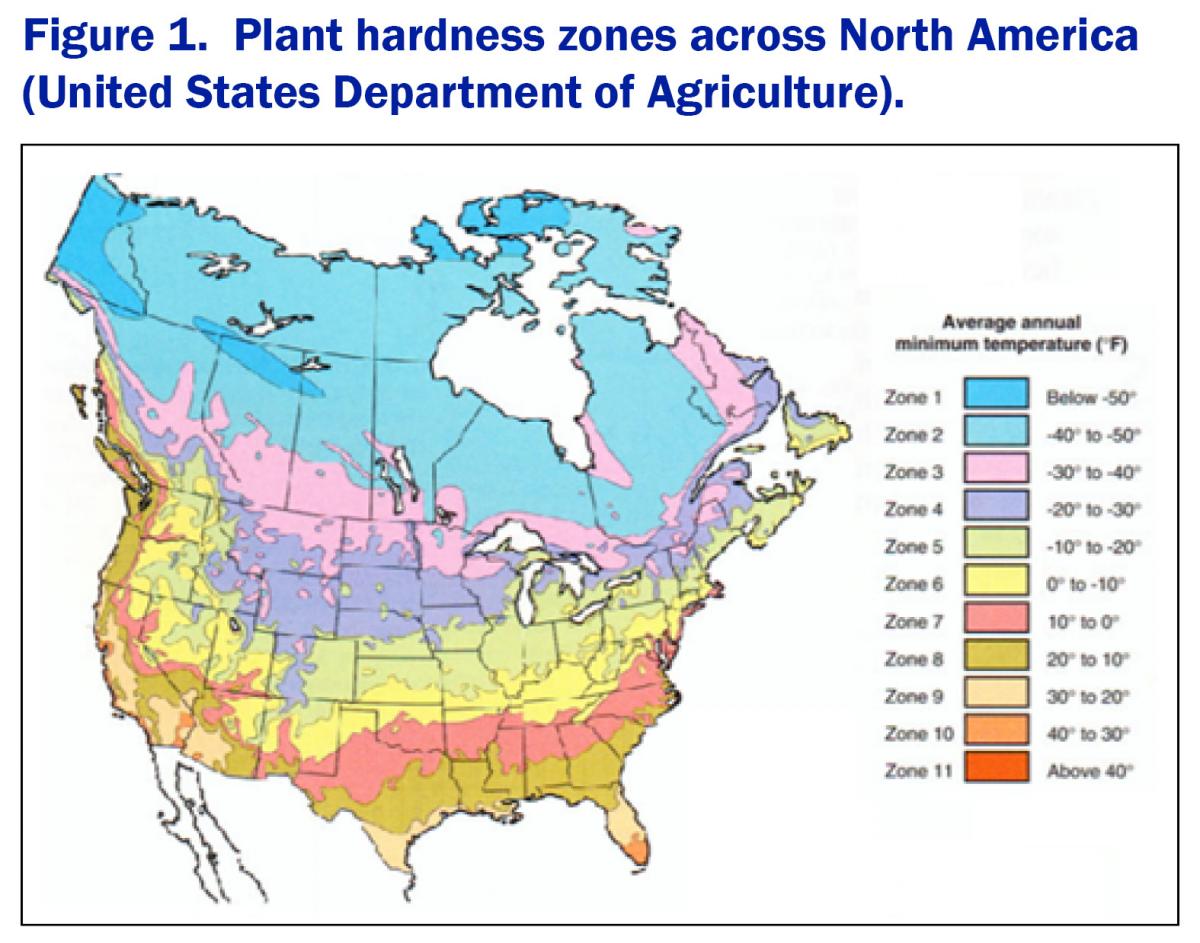

The nature and composition of grain production varies considerably between Canada and the United States. The major difference is the variety of crops grown within each country, with climate being the determining factor. Most of the arable Canadian land doesn’t receive the heat units required to grow corn and soybeans (Figure 1).

In the U.S., corn and soybeans account for more than 55 percent of the acres harvested, but these crops only account for 11 percent of the acres harvested in Canada. Although southwest Ontario could be considered an extension of the corn belt, most Canadian producers feed diets higher in wheat. In the prairie provinces of Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan, canola becomes the largest crop planted, with wheat, lentils/peas and barley following, respectively.

Micro ingredients (amino acids, minerals and vitamins), specialty ingredients (whey and plasma) and feed additives are all largely used in the same ways in both countries. However, due to differences in regulatory status, certain products may only be available in one country and not in the other.

Diet composition

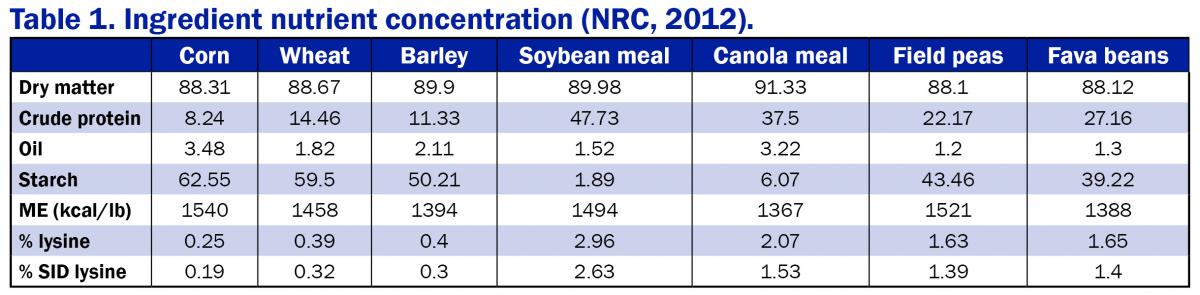

Regardless of location, pigs still require the same amount of nutrients. So when it comes to putting diets together, nutritionists in both countries formulate diets to similar nutrient levels. Table 1 reviews the nutritional content of common feedstuffs.

As mentioned earlier, western Canadian producers use small grains, like wheat and barley, as the base for their diets, which have lower energy content, but higher protein concentration than corn. Although soybean meal (SBM) is the gold standard when it comes to protein sources in swine diets, Canadian producers also use local products, such as peas, fava beans and canola meal, to provide some of the amino acids required by the animal.

Canola meal, like SBM, has to be processed to inhibit naturally present anti-nutritional factors, like tannins, glucosinolates, sinapine and fiber, all of which can negatively affect feed intake. Canadian producers limit the amount of canola meal in nursery and sow diets, but, as pigs grow, they can gradually withstand the anti-nutritional factors that come with 25-percent canola meal inclusion. Peas and fava beans (zero tannin varieties) have similar feed restrictions as SBM.

Another difference between the diets is how energy is measured and included. Canadian nutritionists have been more proactive in adapting the net energy system to evaluate the energy content of feeds and feedstuffs. A large proportion of diets in the U.S. Midwest are formulated using metabolizable energy, which measures the amount of usable energy for pigs to live and grow. The difference between these two energy calculations is net energy accounts for the energy required to metabolize and digest nutrients so they can be used by the pig. More simply stated, net energy is the energy available to the animal for production (growth, lactation and gestation) and maintaining bodily function.

However, it is difficult to determine the net energy content of ingredients and complete feeds, making it more costly to implement. As science continues to progress, U.S. nutritionists will likely adapt to the net energy system.

Western Canadian nursery and lactation diets include wheat, but also supplemental fat or oil to obtain energy levels similar to diets fed in the U.S. Midwest. On top of similar nutrient levels to U.S. diets, nursery diets in western Canada often contain SBM instead of canola meal because of the higher nutrient density and limited anti-nutritional factors. Grow-finish and gestating sow diets in western Canada often have lower energy levels than U.S. diets because these pigs are able to increase feed intake to meet their caloric demands.

Feed costs

In May 2017, farrow-to-finish feed costs per pig, in U.S. dollars, were $84.20 in Ontario, $76.20 in Alberta and $71.54 in Iowa. Multiple factors influence feed costs, like feed efficiency and market weight, but feed costs also tend to be higher in Canada because of the extra cost to import ingredients that are not locally sourced.

Although Canadian and U.S. pork producers are faced with different challenges when it comes to ingredients, they both strive to produce pork that is economical and safe to consume.

About the author: Garrett Rozeboom grew up raising animals for 4-H on a small farm in Michigan. Rozeboom attended Southwest Minnesota State University before transferring to the University of Minnesota where he majored in animal science. After completing his undergraduate degree, Rozeboom earned his master’s degree from the University of Saskatchewan. He soon began working for an independent nutrition consulting group and spent five years in Canada, dividing his time between Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario, before joining Vita Plus in December 2016.

| Category: |

Feed costs Feed ingredients Markets and economics Swine Performance |