Harvesting fall-seeded rye as silage

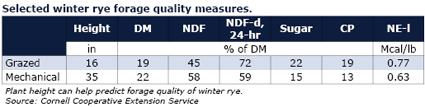

By Jon Urness Spring harvesting of fall-seeded small grain grasses such as rye, triticale, and wheat as haylage has been popular in some areas of the country. Interest in this practice has spread in the Midwest as a source of forage for replacements and the opportunity to maximum forage yield by double-cropping in combination with corn silage. And, with drought-reduced forage yields, some of these feeds may end up in lactating dairy rations. With a climate not unlike the Midwest, the Cornell Cooperative Extension Service in New York has noted that spring harvest timing can get a little tricky because, as heat units increase, crops like winter rye mature very quickly. During the Vita Plus Custom Harvester Meeting held in Madison recently, a custom operator from Pennsylvania commented that it seems like winter rye is often ready to go in the morning, but is over-ripe by afternoon. Cornell recommends harvesting prior to the emergence of heads while still in the boot stage. This normally occurs around mid-May in that part of the country. Typical yields in New York have been 1.5 to 2.5 tons of dry matter per acre and protein levels can be improved with spring applied topdressing of nitrogen.

By Jon Urness Spring harvesting of fall-seeded small grain grasses such as rye, triticale, and wheat as haylage has been popular in some areas of the country. Interest in this practice has spread in the Midwest as a source of forage for replacements and the opportunity to maximum forage yield by double-cropping in combination with corn silage. And, with drought-reduced forage yields, some of these feeds may end up in lactating dairy rations. With a climate not unlike the Midwest, the Cornell Cooperative Extension Service in New York has noted that spring harvest timing can get a little tricky because, as heat units increase, crops like winter rye mature very quickly. During the Vita Plus Custom Harvester Meeting held in Madison recently, a custom operator from Pennsylvania commented that it seems like winter rye is often ready to go in the morning, but is over-ripe by afternoon. Cornell recommends harvesting prior to the emergence of heads while still in the boot stage. This normally occurs around mid-May in that part of the country. Typical yields in New York have been 1.5 to 2.5 tons of dry matter per acre and protein levels can be improved with spring applied topdressing of nitrogen.  University of Wisconsin Extension Agronomist Dr. Dan Undersander recommends harvesting rye at the boot stage when the head is just visible in the leaf whorl for dairy-quality forage. Some producers may want to harvest earlier in order to gain quality and leave time to plant another crop such as corn or sorghum-sudangrass. Yields will be lower with an earlier harvest and Undersander strongly recommends wide-swathing to increase drying rate. In addition, if a conditioner is used, adjust it so that a small amount (1 to 3 percent) of leaf bruising is visible. Paul Craig, an Extension educator from Penn State, is also a proponent of wide-swathing and emphasizes the need for fast wilt in order to concentrate sugars and improve fermentation of rye silage. Craig also recommends using an inoculant to help speed the fermentation process in this finicky-to-ferment feed. Harvest rye at 64 to 67 percent moisture. That probably means starting at 68 percent moisture in order to hit this window. Harvesting too wet will mean some pretty ugly feed with the potential for a clostridial fermentation. Put it up too dry and it won’t pack or ferment well. Finely chop rye for silage. One-half inch isn’t any too fine and you might have to go finer if this stuff starts to get dry. Rye silage does not pack well and packing tractor operators describe it as spongy. Keep those tractors moving and remember the thumb rule of 800 lbs of packing weight for every ton per hour of feed delivery. And be sure to cover this feed with good plastic (preferably Silostop oxygen barrier film under a layer of conventional plastic) and lots of tires. Planting considerations regarding winter rye

University of Wisconsin Extension Agronomist Dr. Dan Undersander recommends harvesting rye at the boot stage when the head is just visible in the leaf whorl for dairy-quality forage. Some producers may want to harvest earlier in order to gain quality and leave time to plant another crop such as corn or sorghum-sudangrass. Yields will be lower with an earlier harvest and Undersander strongly recommends wide-swathing to increase drying rate. In addition, if a conditioner is used, adjust it so that a small amount (1 to 3 percent) of leaf bruising is visible. Paul Craig, an Extension educator from Penn State, is also a proponent of wide-swathing and emphasizes the need for fast wilt in order to concentrate sugars and improve fermentation of rye silage. Craig also recommends using an inoculant to help speed the fermentation process in this finicky-to-ferment feed. Harvest rye at 64 to 67 percent moisture. That probably means starting at 68 percent moisture in order to hit this window. Harvesting too wet will mean some pretty ugly feed with the potential for a clostridial fermentation. Put it up too dry and it won’t pack or ferment well. Finely chop rye for silage. One-half inch isn’t any too fine and you might have to go finer if this stuff starts to get dry. Rye silage does not pack well and packing tractor operators describe it as spongy. Keep those tractors moving and remember the thumb rule of 800 lbs of packing weight for every ton per hour of feed delivery. And be sure to cover this feed with good plastic (preferably Silostop oxygen barrier film under a layer of conventional plastic) and lots of tires. Planting considerations regarding winter rye

- Recommended seeding rates are 90 to 112 pounds per acre and may be increased slightly if planting is delayed to improve seeding density. Later-planted rye will have reduced effectiveness for erosion control.

- Rye responds well to commercial application of N at 40 to 60 pounds per acre. If the source of N is manure or a previous legume crop, 80 pounds per acre may be the economic optimum.

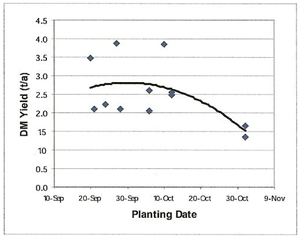

- Fall planting date has a huge impact on subsequent spring forage yields. On average, rye planted by September 20 will yield a full ton of dry matter more than winter rye seeded near the end of October (see table below).

- Winter rye is an excellent cover crop and will help take up excess phosphorus. An estimated 18 pounds of P are removed from the soil for each ton of dry matter harvested.

- Rye does a nice job of reducing soil nitrate levels following fall-applied manure. Based on a fall manure application rate of 40 tons per acre, nitrate levels measured in the spring have been around 190 pounds per acre without rye and almost half that level or 100 pounds per acre when rye was fall planted and spring harvested.

- Subsequent crops of corn will likely experience a yield reduction according to work done at the University of Wisconsin research station in Arlington, Wis. Rye has an extensive root system and can zap soil moisture during a spring when moisture is short. In addition, spring harvest has the potential to delay follow-up corn planting, which can also reduce yields. Also, rye can be an attractive environment for armyworm moths, so producers should watch for that pest as well. Reduced corn yields averaged 13 bushels per acre over three years at Arlington. Subsequent crops of alfalfa or soybeans didn’t seem to respond negatively to spring-harvested rye.

Effect of planting date on rye forage yield in southern Wisconsin.  While fall-seeded grasses such as rye are of particular interest following a season of reduced forage yields because of drought, flooding or winter kill, alfalfa remains the mainstay forage in the Midwest where we’re able to produce high quality and high yields of alfalfa haylage. But when forage supplies are tight, it’s good to know we have alternative sources of forage available. About the author: Jon Urness is the Vita Plus national forage specialist. He grew up on his family’s five-generation homestead dairy near Black Earth, Wis. and still lives there today. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1977 with a bachelor’s degree in agricultural journalism. Since 1992, Urness has provided on-farm dairy nutrition consulting in southwest Wisconsin as a Vita Plus employee owner. He has also taken on the forage marketing responsibilities outside of the traditional Vita Plus market.

While fall-seeded grasses such as rye are of particular interest following a season of reduced forage yields because of drought, flooding or winter kill, alfalfa remains the mainstay forage in the Midwest where we’re able to produce high quality and high yields of alfalfa haylage. But when forage supplies are tight, it’s good to know we have alternative sources of forage available. About the author: Jon Urness is the Vita Plus national forage specialist. He grew up on his family’s five-generation homestead dairy near Black Earth, Wis. and still lives there today. He graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1977 with a bachelor’s degree in agricultural journalism. Since 1992, Urness has provided on-farm dairy nutrition consulting in southwest Wisconsin as a Vita Plus employee owner. He has also taken on the forage marketing responsibilities outside of the traditional Vita Plus market.

| Category: |

Crop varieties Dairy Performance Forage harvesting Silages |