Grow heifers BEFORE calving

By Barry Visser

By Barry VisserThe goal of most heifer replacement programs is to raise high-quality, healthy heifers in an efficient and economical manner. These heifers have the genetics, frame, body condition, and management background to conceive in a timely manner, reach their potential for high first-lactation milk yield, and become profitable replacements to the herd.

This past winter, I participated in a series of producer discussions with Dr. Michael Overton, Elanco Animal Health, to discuss the dynamics of heifer rearing and the costs associated with inadequate heifer growth.

The age at first calving has been trending downward the past decade. Today, many herds bring heifers into the milking herd at 22 months or even younger. Early calving has been promoted because it gets heifers in the milking string faster, decreases heifer numbers, and reduces heifer feed and rearing costs. For some dairies, this reduction has been positive for lifetime milk production, but, for many, it has not. The primary difference is bodyweight at first calving.

There is a philosophical disconnect between age at first calving and average daily gain (ADG) on many dairies. Bodyweight of a heifer at the time of first calving is a proxy for growth and size. If heifers have not reached the desired size at calving, they will continue to grow during lactation. This is much less efficient and happens at the expense of milk production. Overton estimates that 1 pound of growth during lactation cost 7 pounds of milk. Dr. Gavin Staley, a technical service veterinarian with Diamond V, uses a rule of thumb that 60 pounds heavier weight at calving equates to 3 to 4 pounds more milk production per day across the whole herd.

There is a philosophical disconnect between age at first calving and average daily gain (ADG) on many dairies. Bodyweight of a heifer at the time of first calving is a proxy for growth and size. If heifers have not reached the desired size at calving, they will continue to grow during lactation. This is much less efficient and happens at the expense of milk production. Overton estimates that 1 pound of growth during lactation cost 7 pounds of milk. Dr. Gavin Staley, a technical service veterinarian with Diamond V, uses a rule of thumb that 60 pounds heavier weight at calving equates to 3 to 4 pounds more milk production per day across the whole herd.

How big should heifers be at the time of calving? To answer this question, a farm must know the average weight of mature cows in the herd. Cows typically do not reach their mature size until their third to fourth lactation. A subset of these cows between 80 and 120 days in milk should be used as the predictor for mature size. Overton cautions not to use the last load of cull cows that were long DIM with excess body condition.

Overton shares that fresh heifers need to weigh 85% of the mature bodyweight post-calving. If springing heifers are easier to weigh, they should be closer to 95% of this mature bodyweight shortly before calving. Assuming the average mature bodyweight in your herd is 1,500 pounds, a springing heifer should weigh approximately 1,425 pounds. To reach these goals, farms must maintain an ambitious daily rate of gain during the rearing process.

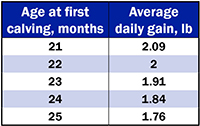

The chart to the right shows the average daily growth rate needed to achieve an average Holstein springer weight of 1,425 pounds. Calf birth weight of 85 pounds was subtracted to determine a desired weight gain of 1,340 pounds from birth to calving.

The chart to the right shows the average daily growth rate needed to achieve an average Holstein springer weight of 1,425 pounds. Calf birth weight of 85 pounds was subtracted to determine a desired weight gain of 1,340 pounds from birth to calving.

Striving to reach these growth rates all year round is a challenge in many heifer rearing systems. However, if we can get heifers weighing close to 85% of their mature bodyweight at calving, much less growth is required in first lactation.

Weight at calving not only determines first-lactation performance, it has a profound impact on the lifetime performance and your overall herd performance. In an extensive record analysis, Staley concluded that first-lactation milk production determines the upper limit for the whole herd. He stated, “A herd cannot outperform the production set by first-lactation animals.”

Staley established four guidelines after reviewing trends in nearly a half-million records:

- First-lactation production at 10 weeks (approximate peak production) will be very near the herd production average across all lactations.

- At five weeks post-calving, second-lactation cows will produce 30 pounds more milk than first-lactation heifers.

- At five weeks post-calving, third-lactation cows will produce 8 to 10 pounds more milk than second-lactation cows.

- The above differences appear to be independent of milking frequency and level of production.

If your first lactation heifers do not meet production expectations, it may be time to implement a more intensive program to measure bodyweight. If you are not meeting growth goals, an evaluation of your heifer-rearing program may identify bottlenecks. In the meantime, delayed breeding can be a short-term solution so that heifers are reaching their weight goals at calving.

This article was written for the author’s “Something to Ruminate On” column in the February 22, 2020 issue of Dairy Star.

About the author: Barry Visser is a dairy technical specialist based in Minnesota. He grew up on his family’s dairy farm in northwest Minnesota. Visser received his bachelor’s degree in animal science from the University of Minnesota in 1994. He worked as a dairy nutritionist for four years before returning to graduate school to earn his master’s degree in dairy cattle nutrition. His research focused primarily on transition cows and minimizing pre- and post-calving metabolic challenges. While a graduate student, Visser also worked as an assistant herdsman for the University of Minneosta St. Paul dairy herd. At Vita Plus, Visser works with fellow employee owners to troubleshoot farm nutrition, forage quality and management challenges.

| Category: |

Calf and heifer nutrition Calf nutrition Dairy Performance Feed quality and nutrition Milk production and components Transition and reproduction |